The Messenger

As a boy, Len Necefer worked and played among the sandstone canyons, desert mesas and forested buttes of the Bears Ears area of southeastern Utah.

A member of the Navajo nation, he tended the family sheep herd with older cousins, clambered over world-class rock-climbing terrain and gathered medicinal and ceremonial plants with his grandfather, a uranium miner who lost a lung to silicosis before becoming a traditional healer later in life.

The seeds of these childhood adventures grew into a career with many shoots but one common root: a conservation ethic that calls for protecting the natural and cultural heritage of America’s wildlands.

“All of the threads tie back to taking care of the land, basically,” Necefer, e’11, says of his varied career interests.

As a scholar, the assistant professor in the University of Arizona’s American Indian Studies program and Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy teaches students natural resource policy and conducts research on environmental and indigenous nations issues, particularly the connections between national energy policy and traditional subsistence hunting in Alaska, where some indigenous communities get 50% to 80% of their food from the land.

An avid adventurer, he has made films and written articles for outdoor magazines about his trips to culturally significant sites such as Cochise Stronghold in Arizona, a rock-climbing outing among imposing granite ramparts that once sheltered the Apache chief Cochise and his people; and Sisnaajiní in Colorado, a ski mountaineering trek to one of the Navajos’ most sacred peaks, the fourteener also known as Blanca Peak, in the Sangre de Cristo Range.

As an entrepreneur, Necefer founded Natives Outdoors, an outdoor apparel company that grew out of a social media campaign he initiated to share the Native perspective on the outdoors, including a bid to revive the original indigenous place names of popular adventure destinations.

“The campaign originally started as a platform to share stories,” Necefer says, “but I realized, ‘Wow, we could actually make some cool products,’ because what’s happening in the outdoor industry quite a bit is Native designs are used on products, but the profits don’t benefit Native communities.”

Discovering, from his own research, that most of America’s national parks are within 100 miles of an Indian reservation, he realized the economic development potential that the $400 billion outdoor recreation industry could offer to Native Americans, who experience a 26% poverty rate, the highest of any racial group in the United States and more than double the national average.

Necefer followed his love for adventure sports to form Natives Outdoors, offering products designed by indigenous people and leading the charge to protect wildlands like Bears Ears (right).

L: GREG BALKIN | R: JOHNNY ADOLPHSON, DREAMSTIME.COM

But money, while significant, really isn’t the main issue for Necefer.

“For me, it’s more importantly about cultural and language revitalization,” he says, “because so much of the culture and history of Native people is tied to landscapes and can’t be taught in a classroom effectively.”

Many Native communities are already “rich in their culture and land,” he argues. But those valuable commodities, too—as Necefer has learned firsthand—are also under threat.

Necefer was working at the U.S. Department of Energy as an analyst and project monitor in the Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs when the Trump administration began working to open the Bears Ears National Monument and the Arctic Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas development.

Drawing on his mechanical engineering training at KU and Carnegie Mellon, where he earned a PhD, his work focused on helping Native communities develop and maintain renewable energy projects. He’d seen those efforts stymied. At one point, he was told to remove all references to climate change from a report he wrote. He refused.

“I remember telling my boss, ‘If they open up the refuge, I’m gone,’” Necefer recalls. Then on Dec. 4, 2017, in Salt Lake City, President Trump announced his decision to slash the 1.3-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, established by President Barack Obama in 2016, by 85%. He cut another national monument, Grand Staircase-Escalante, established by President Bill Clinton in 1996, by nearly half. All told, the reduction opened to extractive industries nearly 2 million acres of protected land, the largest environmental rollback in U.S. history.

Later that month, the president signed a tax bill that also eliminated restrictions on oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska.

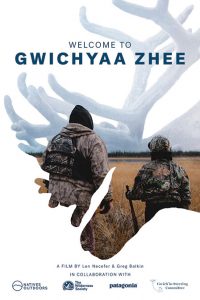

In “Welcome to Gwichyaa Zhee,” a short film Necefer made with the help of a grant from the Wilderness Society and support from outdoor retailer Patagonia, he recounts his reaction to the Alaska decision.

“I had no words. From growing up with energy development all around me on the Navajo Nation, I knew exactly what the impacts would be.”

Necefer says the thousands of Navajo men recruited to mine uranium on the 27,000-square-mile reservation in the 1950s were not supplied with respirators and other safety equipment: His grandfather, Henry Lee, lost his left lung to silicosis when he was only 40, and when Necefer was a toddler “a lot of men in their 50s and 60s in the community were dying from cancers or respiratory illnesses.” A nearby coal-fired power plant and extensive oil and gas development contributed to air pollution so bad that “in winter you could taste the air,” Necefer says.

Determined to take action, he quit his job at the Department of Energy. A week later, he was in Salt Lake City, protesting the signing of the Bears Ears reduction.

“Welcome to Gwichyaa Zhee,” released in March, explores the connections between threats to Bears Ears and the Arctic Refuge through the stories and perspectives of Necefer’s people, the Diné (Navajo), and the Gwich’in, an indigenous community in the Arctic Circle who have depended for centuries on the Porcupine Caribou herd for survival.

“Len is an amazing storyteller,” says Lulu Gephart, the film’s producer and senior director of marketing for the Wilderness Society, which has been working since the 1970s to protect the Arctic Refuge. “The film started with understanding his connection to the refuge, that he didn’t just understand the issues in an academic sense, but he had personal relationships there, he had spent time there. He just has a remarkable knack for finding people with incredible stories.”

“Welcome to Gwichyaa Zhee” follows another film, “Messengers: A Running Story of Bears Ears and Escalante,” that documents a marathon relay Necefer organized in January 2018. A group of friends ran 250 miles across the Bears Ears and Grand Escalante monuments in a single weekend to see for themselves—and to show the world—the natural wonders and important archaeological sites (more than 100,000 at Bears Ears alone) left unprotected by the reduction—a decision, the film points out, that was made by leaders who have never set foot on the land they are opening to industry.

The Bears Ears archaeological sites date back 20,000 years. “For the five tribes that came together and lobbied for the creation of this monument, these places are still alive and they are the places people take their kids to teach the history of their connection to the place,” Necefer says. “They are simply preserving their Library of Congress.”

Through Natives Outdoors, Necefer consults with tribes, state governments, community groups and the outdoor industry to help ensure that any recreational development on Native land—the construction of trails or granting of rock-climbing access, for example—benefits the people, rather than threatening their land and way of life, as has sometimes been the case.

“He’s painting a picture of a better path that the outdoor and environmental communities can take in thinking about their relationship to the outdoors,” Gephart says. Those groups have always cared about nature, she adds, “but they’ve never really been challenged to think about it through the lens of the people who’ve been there and have thousands of years of history of knowing how to take care of nature.”

Necefer, with his credibility among a range of disparate groups—Native, outdoor recreation, environmental, academic—is issuing that challenge, and doing it in a highly effective manner, Gephart says.

“He’s been really great about being able to focus those conversations on what we have in common, going about it in a really amazing way that brings more people into the conversation without alienating anyone. That’s the sweet spot where I see him operating now.”

So far this summer, he has led a summit in Colorado that brought together leaders of a dozen tribes and the state’s lieutenant governor to search for common ground and discuss ways that Native communities can participate in the outdoor industry. He is working with mountain- and rock-climbing advocacy groups such as the American Alpine Club and the Access Fund to establish best practices to help guide the outdoor industry on engaging with tribes on land issues and recreation opportunities, and he chairs the board of Shift, an annual festival held in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, that’s a kind of Davos Forum for the nature set, gathering leaders and thinkers from outdoor recreation, conservation and public health.

“It’s not the stuff we have, the money we make or the car we drive that makes a good life,” Necefer says of Natives’ value of family, community and environment. “The Gwich’in are rich in their culture and land, and we’re threatening to take that from them.”

GREG BALKIN

On June 20, Necefer testified before Congress, addressing the House Energy and Mineral Resources Subcommittee to urge support of HR 3225, the “Restoring Community Impact and Public Protections In Oil and Gas Leasing Act,” which seeks to restore 30-day public comment periods that allow citizens to make their views known on proposed oil and gas leases on public land.

He told his story of learning about the impacts of energy development on Native communities by observing his grandfather’s “tail,” the tubes that ran across his face and down his back to a portable oxygen tank that he carried everywhere.

“I pursued higher education because at first I was angry about this history,” Necefer testified. “And then later I felt responsible about doing something about it.”

In June he made a return trip to Fort Yukon, Alaska, to visit his Gwich’in friends. This time he took with him four Patagonia-sponsored athletes, including ultrarunner Clare Gallagher, who also participated in the Bears Ears relay.

She has called Necefer “the go-to man” for information about the deep indigenous imprint on popular outdoor destinations that once were Native land but are now misrepresented (as Necefer himself puts it) by “the myth that these are untouched wilderness areas.”

“The campaign to save Bears Ears has been so influential in the outdoor industry,” Gallagher says, “but the outdoor industry has to realize that we are just the frosting of this seven-layer cake to the history of this land. Len could tell you 10 million things that most people who’ve been going to places like Indian Creek for years wouldn’t know.”

The backlash brought on by the rollbacks at Bears Ears and Escalante inspired thousands to protest and drew national media attention. The Gwich’in fight has been much quieter, the spotlight much harder to command. “Welcome to Gwichyaa Zhee” is a modest attempt to do something about that, while also pointing out a stark reality: That the Gwich’in face some of the same challenges as the Navajo is not simply a coincidence.

“Making this film we were really interested in demonstrating that it’s not just, ‘Shoot, this one bad thing happened to this one community,’” Gephart says. “The Gwich’in and the Navajo face the same inequities because the whole system is set up to continually and repetitively perpetuate inequity. These seemingly one-off incidents show that this is how the system works, that it is built to work against these communities.”

But as pieces of cinema, as works of art, as stories, “Welcome to Gwichyaa Zhee” and “Messengers” function at a more primal level. Each demonstrates that Native people fighting for control of their land are fighting for survival—because their relationship to the land is their life.

“Len is one of those people who’s not just going to stand by when he sees injustice and do nothing about it,” Gephart says. “It’s rare to meet someone who’s that brave. He’s not only got the academic smarts to make his arguments, but also the bravery to stand up to these institutions and to the unpredictability of what the repercussions might be. It’s pretty cool to see that in action.”

The battle over Bears Ears has drawn lots of support from Natives and non-Natives alike, Necefer notes. “Our voice was amplified because people showed up for us, but the Gwich’in are fighting the same battle and they deserve the same support,” he says in the film. “In a time when Native communities still feel invisible to the rest of our country, people need to continue uniting around these issues. If we show up for the Gwich’in, maybe their voice will finally be heard.”

During his leg of the Bears Ears run in “Messengers,” Necefer’s emotions surged as he approached the twin buttes that give the area its name.

“It was one of the first times I felt that people other than my own community, people who had no connection to Native issues, actually began to care about it and that led me to break down,” he explains. “I was like, ‘Wow, I finally don’t feel invisible anymore.”’

Before they became a horse culture, the Navajo relied on message runners—“ultramarathoners, essentially,” Necefer says—to carry communications between the various bands spread across their vast territory. Growing up, he heard stories of his great-great-grandfather running messages over mountains. Now it’s his turn. Through films, magazine stories and savvy social media use, he’s spreading the message that indigenous ways of life, so easily and frequently stereotyped as impoverished, are valuable.

New ways of saying old ways are worth protecting.

“Where I’m trying to start is, let’s build on these shared values, the kinds of things we care about together, and then try to work out how we can take steps to ensure that, first, my community is not left out of these discussions,” Necefer says. “And second, that public lands are managed in a way that benefits all Americans.”

The fate of Bears Ears, Grand Staircase-Escalante and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge remain uncertain, tied up in court challenges that may take years to resolve.

But time is not the problem for people who have called these areas home for millennia. After all, the wildlands and protected wilderness areas we all enjoy, Len Necefer points out, exist because of their centuries-long stewardship of the land. Rather than dismiss or ignore the Native ways that have protected these natural wonders for us, maybe we should learn from them.